I just read something I wrote in 2011 the day after Siri was announced as a feature of iPhone 4S. Unfortunately it was little more than a regurgitation of Apple’s own marketing copy and I regret not having written more of my own serious thoughts and feelings about what the future might hold for conversational AI. I’m a bit late to the party, but this week I’ve been trying out ChatGPT and don’t want to miss the same opportunity to document my reaction in real-time.

What is it?

GPT stands for generative pre-trained transformer. It’s an artificial intelligence model developed by OpenAI to produce human-like language. The first iteration was InstructGPT, a tool used to create “coherent and appropriate step-by-step instructions for a given task”. ChatGPT builds on InstructGPT by having the ability to carry on an interactive conversation and react to questions, sometimes even with questions of its own. And it writes! It can write poetry, essays, short stories, and even code in a surprising number of programming languages.

If Siri and Alexa are smart at listening and understanding what you’re asking, ChatGPT brings the smarts to the other half of the conversation, not just recalling terse facts and figures the way today’s conversational assistants do, but providing in many cases whole paragraphs of apparently off-the-cuff explanation and analysis (if you ask it the same question twice, it words its answer differently the second time).

First contact

I’d heard of ChatGPT a few times in water-cooler conversation around the office (the alpha version officially released to the public in November 2022), but my first experience with it was related to JavaScript trainings I’ve been doing at work. Once a week I’ve been holding a class with my junior engineers and a couple developers from another team to teach them JavaScript, and I’ve been handing out optional homework. We’ve recently been learning about strings and string manipulation and a couple weeks ago I challenged them to write a script for turning English text into Pig Latin.

One of my colleagues, on a whim, decided to punt this challenge over to ChatGPT. We’d had a conversation earlier where I’d said, essentially, “there’s no way it actually writes good code”, so earlier this week he presented this to me without telling me where it came from (except to say he hadn’t written it himself) and asked me to critique it:

function translateToPigLatin(str) {

// Split the string into an array of words

const words = str.split(' ');

// Translate each word to Pig Latin

const pigLatinWords = words.map(word => {

// If the word starts with a vowel, just add "way" to the end

if (/^[aeiou]/.test(word)) {

return `${word}way`;

}

// Otherwise, move the first consonant cluster to the end and add "ay"

const consonantCluster = word.match(/^[^aeiou]+/)[0];

return `${word.substring(consonantCluster.length)}${consonantCluster}ay`;

});

// Join the translated words back into a single string and return it

return pigLatinWords.join(' ');

}Assuming he’d found it on Stack Overflow or some such, I told him it looked pretty good to me. Regular expressions are a clever way to solve the problem and the names of the function and variables are all decently verbose and self-documenting. I was honestly a bit shook when he sprung the twist on me that it’d been written by an artificial intelligence.

Getting to know you

So I had to sign up for an account and see what all the fuss was about myself. My first test was asking ChatGPT to write a simple ServiceNow GlideRecord query. A different colleague had told me weeks before that ChatGPT didn’t know anything about ServiceNow, so I wasn’t optimistic, but it surprised me with a flawless GlideRecord script.

So then I threw something at it that I knew from prior experience was non-trivial, “Write me a GlideRecord script that chooses random incidents closed in the last week”. Here’s the code it wrote (for brevity, in this and all later examples, I’m only posting the code, but ChatGPT impressively always provides a lot of context along with scripts, explaining what they do and how to use them):

// Create a new GlideRecord object

var gr = new GlideRecord('incident');

// Set a query condition to only return incidents that were closed in the last week

gr.addQuery('closed_at', '>', gs.daysAgo(7));

gr.addQuery('closed_at', '<=', gs.daysAgo(0));

// Query the database

gr.query();

// If there are any records returned, choose a random one

if (gr.hasNext()) {

// Get the total number of returned records

var count = gr.getRowCount();

// Choose a random number between 0 and the total number of returned records

var randomIndex = Math.floor(Math.random() * count);

// Go to the record at the chosen random index

gr.setLimit(1, randomIndex);

gr.query();

// Do something with the random incident record

// ...

}The simplicity of this code astounded me, particularly its use of the setLimit method with a second parameter. I never knew setLimit had a second parameter, so I asked it a follow-up question, “What’s the second parameter on gr.setLimit()?”. It replied, “[the second parameter] is the starting index for the returned records. The index is zero-based, so a value of 0 will start at the first record.”

For a brief moment, ChatGPT had me completely snowed. It seemed so confident! I genuinely believed this thing was so good at understanding and writing code that it was even teaching me, a seasoned senior engineer, things I never knew. And I honestly got a bit scared I might be a washed-up dinosaur in a few years and need to pivot to some new career. That is, until I consulted the documentation and tried running the script myself.

The documentation knows nothing about a second parameter on setLimit, and of course the code always returns the same incident record, the first one in the data set. So, as impressive as ChatGPT’s code-writing skills appear to be on the surface, it’s clear it makes mistakes. My theory is it’s conflating GlideRecord’s setLimit method with a setLimit method from some other library or framework (and the eagle-eyed will notice one other mistake in the way it uses GlideRecord in the example above). The problem is it’s not quite able to accurately contextualize all the knowledge it possesses. Will it get better at this eventually? Is it only a matter of time before it could realistically replace a human software engineer?

Better than Googling

I’m not worried this thing will put me out of a job, at least not in the short term (but more on that in a bit). Rather than fearing and avoiding it, I’m trying to embrace it as a new tool to make me faster and more efficient at work—the same way a calculator makes math easier. The other day I asked it to write me a GlideDateTime script to get the first day of the month three months ago. It gave me this:

var gdt = new GlideDateTime();

gdt.addMonths(-3);

gdt.setDayOfMonth(1);Now, of course, I already know how to use GlideDateTime. At least, I know it has methods to do what I needed to do in this case, I just don’t always remember the names of the methods off the top of my head. Could I have Googled this or consulted documentation to remind myself of the method names I needed here? Absolutely (the not-so-secret secret is this is what I do all day!), but then I would’ve had to scroll up and down through the list of methods to identify the right ones, and asking ChatGPT turned out to be a very convenient shortcut.

Of course, it’s a shortcut with some serious caveats. When I ran this code I could see it was giving me the right date, but GlideDateTime comes with a time component and I noticed that time component was still set to the current time right now. So I asked, “Can I set the time to midnight, also?”, to which it replied with this additional code snippet:

gdt.setTime("00:00:00");The problem here is, like in the previous example, GlideDateTime has no setTime method. By this time I’d read in the FAQ that the AI model has been trained to admit its own mistakes, so I tried calling it out on the carpet. It replied, “I apologize for the mistake in my previous response. You are correct that there is no setTime method on the GlideDateTime class.” But then it proceeded with an alternative method:

var dateString = gdt.getValue();

dateString = dateString.split(' ')[0] + " 00:00:00";

gdt.setValue(dateString);This code would work—my first thought was, “that’s one way to do it”—but I’m actually not a fan of splitting the string and taking the zeroth index to preserve the date part. That’s a bit obtuse and may not be the easiest for someone coming along later to read and maintain. GlideDateTime has a getDate method, so my final code used that instead because it’s just clearer and hopefully less error prone, but I didn’t learn this from ChatGPT.

gdt.setValue(gdt.getDate() + ' 00:00:00');Caveats aside, I do think using ChatGPT to produce code is a step above Googling and I think I’ll continue to use it this way at work. It’s one more tool in my toolbox alongside API docs, Stack Overflow, and Google, and perhaps it’s the fastest of these resources.

Peering into the crystal ball

I don’t know if improvement will come rapidly as they throw more and more data points at it, or if improvement will come in slow and steady tweaks to how the model carefully sifts the vast amount of things it knows (undoubtedly both). Surely some of what I’m about to say comes from the hubris and confirmation bias of being a senior engineer myself—the main reason I’m writing this down is to see how wrong or right I am in five, ten, twenty years.

I think someday we will produce most software simply by asking an AI to write it for us, but there will always be a need for knowledgeable humans to review that code and debug it. I don’t just mean the steps typically carried out by quality assurance and user acceptance testing (we’ll still need those humans, too), but the steps a human usually does running their own code and debugging it, verifying it does what they think it should do—and these are arguably the hardest part of programming!1

ChatGPT today is like an inexperienced junior dev, and maybe over time it will become a hyper-competent junior, but it will always remain a junior. It will always need the nuance and subtlety of a human senior engineer to massage its output into something better—something more performant, more poetic, more practical to read and maintain later. This means the learning curve for good software engineers will get steeper. There may not be a lot of work for human junior devs anymore, so the path to becoming a sought-after senior dev will be a lot tougher.

Or maybe the opposite will happen. Maybe this will lower the bar making every developer essentially a senior engineer. Not only can tools like ChatGPT write most of the code themselves under human supervision, but ChatGPT in its current form is an amazing teacher and will only get better over time. Being able not only to get clear and cogent instruction from it, but also to ask it follow-up questions and get helpful clarifying responses, will give everyone the ability to level up their skills faster than ever before.

I do worry as more and more people start to rely on something like ChatGPT it will become a crutch, making us dumber in the long run and resulting in buggier, less-performant apps. I can imagine a day not far from now where the majority of code is written by artificial intelligences directed by humans who haven’t bothered leveling up their skills and who have no clue how to debug or improve it, so we just suffer with bloated, glitchy software. But am I overreacting? Have there been similar overreactions in the past to things like Google, Wikipedia, and Siri that turned out not to ruin the world but instead improve and enrich it, allowing us to work smarter and harder in less time?

For now, ChatGPT at least seems like an amazing tool for synthesizing documentation into short, quick answers to questions. Assuming you check its work, it’s a great shortcut for getting stuff done faster. I’ll probably use ChatGPT a lot at work, but just as I would rarely lift something straight from Stack Overflow without refactoring and/or improving it myself, I’ll always do my best to filter what the AI gives me through my own skills and years of experience.

Theology, poetry, and short stories

Lastly, I want to share some other fun I’ve had with ChatGPT. I’ve asked it several theological questions. It seems to have been fed a lot of information about religion and spirituality but, again, doesn’t quite know how to properly differentiate and synthesize it all. I’ve asked it to explain the Trinity to me a handful of times and sometimes it gets the details right, other times it variously gives me modalist, tritheist, or subordinationist answers. I’ve asked it about the difference between biblical and systematic theology, and asked it to give me a biblical theological interpretation of Hosea, which it was able to do but didn’t mention Christ at all. I followed that up with asking for a Christotelic interpretation of Hosea and it did a much better job.

I asked it the other day to write me a haiku, which ended up pretty hilarious. It kept writing the middle line with eight syllables instead of seven, and every time I pointed out its mistake it would apologize and try again, only to fail again. When it finally wrote a haiku with nine syllables in the middle line, I gave up and told it, “You’re not very good at writing haikus yet.”

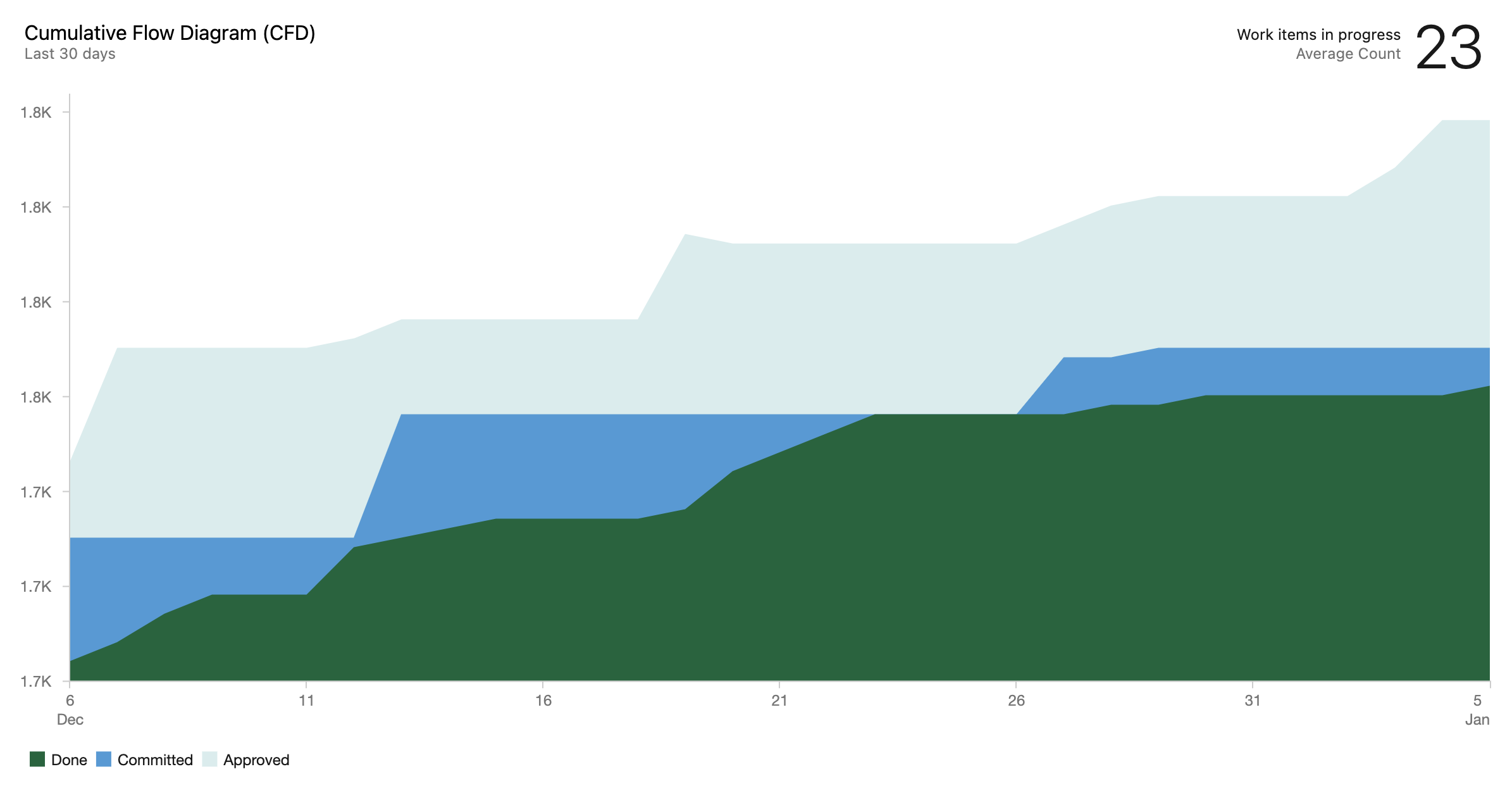

Perhaps the best thing it’s written for me so far was a short story about the lines in a cumulative flow diagram, a chart that shows over time how work moves from to-do to doing to done. Since our team follows agile scrum and commits batches of work in two-week iterations (sprints), our middle (doing) line should always look like a staircase, jumping straight up when we bring in work at the start of the sprint then staying flat throughout the sprint, and the bottom (done) line should climb up at a constant slope as we complete items throughout the sprint. Ideally, if we’re able to complete our whole sprint commitment, the done line will just barely “kiss” the doing line right at the end of the sprint before the doing line shoots up again when we take on new work for the next sprint.

Completing our sprint goal has been a major emphasis of our team building plan, so I’ve made no small fuss over the done line “kissing” the doing line every single sprint. So I had the idea to ask ChatGPT to write me a story about the lines in a cumulative flow diagram kissing. Here’s what it came up with:

Once there were two lines on a cumulative flow diagram, one representing the work that had been completed and the other representing the work that was still in progress. They had been living side by side on the chart for as long as anyone could remember, but they had never really paid much attention to each other.

But one day, something changed. The line representing the work that had been completed glanced over at the other line and was struck by how beautiful she looked. The way she flowed across the page, always moving forward and never looking back, was truly mesmerizing.

And so, the line representing the work that had been completed leaned over and kissed the other line gently on the cheek. It was a small gesture, but it meant the world to the line representing the work that was still in progress.

From that moment on, the two lines were inseparable. They moved through the cumulative flow diagram together, always supporting and encouraging each other. And as they progressed, they fell more and more in love, until they were completely intertwined, a perfect representation of the work that had been accomplished and the work that was still to come.

The lines in the cumulative flow diagram lived happily ever after, their love forever captured in the lines and shapes of the chart.

Brilliant, right?

Conclusion

I hope I’ve captured a decent flavor of where my thoughts and feelings are currently. I think some people are scared artificial intelligence will one day achieve sentience and then we’ll have a big moral quandary on our hands, but I’m honestly not scared of that at all. At the moment I suppose I’m a bit anxious about AI’s ability to replace software engineers entirely, but I assure myself that it will never be completely without faults, that my human sensibilities will always be important for the production of good code, and that I should embrace AI as an awesome tool to make me more efficient and productive. Only time will tell, I guess.

-

I knew this myself, of course, but I’m also taking a cue here from my favorite podcaster, John Siracusa. Skip to about six minutes into episode 516 of Accidental Tech Podcast (chapter 3 if your podcast player supports chapters) for their discussion of code written by artificial intelligences. ↩